What We Do

Adaptation, Relocation, Marginalization: contradictions in the governance of environmental mobility in African cities

by Achilles Kallergis

Environmental mobility has gained increased interest in academic, policy, and media circles). Speculative discourses of an imminent climate migration crisis have elevated environmental mobility into a global issue, underlining the need for multi-level governance, international cooperation, the development of norms and processes, and the recognition of migration as an important adaptation strategy. The focus of most discussions has been centered on the implications of future potential large-scale movements from South to North countries. Such discourses usually adopt a securitization narrative where climate mobility is perceived as an unfolding calamity, a crisis of serious yet unknown proportions, that requires new norms and policies, as well as rapid and transformative actions that encompass distinct forms of mobility in the efforts to adapt to a changing climate. Somewhat paradoxically, less attention has been given to the implications of environmental mobility within smaller geographies – particularly within borders – through empirical evidence and most rigorous future estimates point to shorter movements in time, space due to climate variability.

Such mobility trends are apparent in cities of Africa, a region that undergoes intense urbanization faces extensive poverty and vulnerability to climate change, and where a significant share of environmental mobility is expected to be directed towards its cities. Placing environmental mobility within the broader context of the region’s urbanization – what admittedly is the dominant mobility process in the region – it becomes clearer how temporarily and spatially, mobility due to environmental change is manifested and negotiated locally, with low-income urban neighborhoods at environmental risk, representing the destination areas for migrants. The role of these areas has been increasingly recognized in the growing environmental migration scholarship. However, little attention has been given to the contradictions that occur between international and regional norm-setting that aim to improve mobility outcomes and incorporate movements due to environmental events, and national and local urban processes the seek to slow, restrict, and reconfigure mobility towards and within rapidly growing cities.

The recent proliferation of regional agreements and norms that govern mobility and that recognize environmental change and extreme weather events as one of the region’s mobility drivers provides an urgent call for action. The African Union’s 2018 Free Movement Protocol stipulates the “gradual removal … of obstacles to the free movement of persons … and the right of residence and establishment” through individual, bilateral and sub-regional measures. Agenda 2063, calls for a “free movement of people, goods, services, and capital” (Agenda 2063: 86) and references the impacts of climate change in the region, which are “expected to be severe, pervasive, cross-sectoral, long-term, and in several cases, irreversible…inducing population displacement, spontaneous large-scale migration, land encroachment, and creating refugees.” (Agenda 2063: 105).

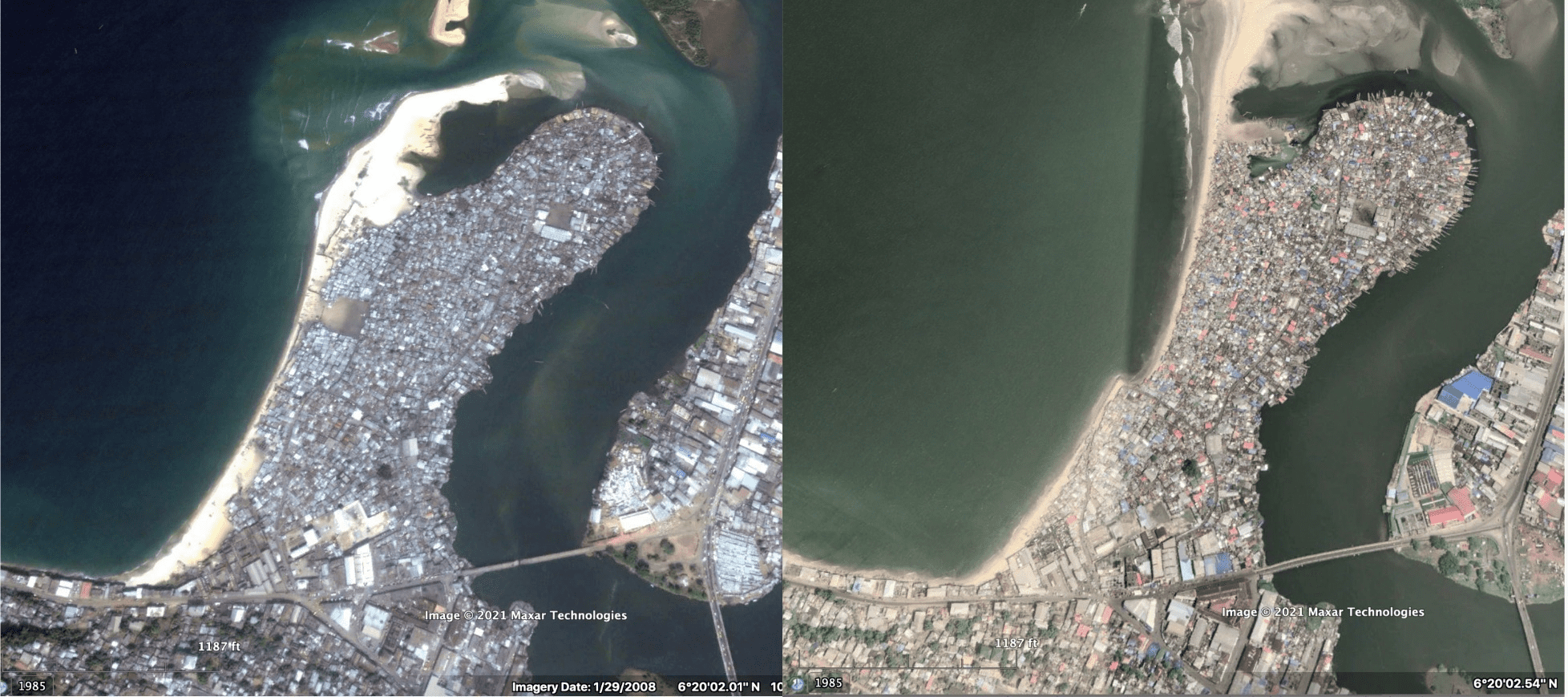

These contradictions become obvious in the context of a government-led relocation process in Monrovia, Liberia. In this case, efforts to adapt and protect populations from the effects of climate change in the coastal community of West Point result in relocation practices that fail to meaningfully address the issue. Moreover, these practices can potentially lead to the protracted marginalization of those facing environmental risk. West Point is one of the largest settlements in Monrovia with an approximate population of 60,000 to 75,000 people. Due to its location and dense built-up area, the neighborhood is vulnerable to sea level rise and related coastal hazards, with coastal erosion and inundation being frequent challenges. As the land area changes, structures are constantly rebuilt and densities are shifting. “Displacement is cyclical in West Point. With each high tide and converging sea surge, the abrasive currents and high-energy waves erode more of the shoreline. After each event, there is less room to rebuild, resulting in higher densities, smaller lots, and new homes at risk.”

Figure 1 Coastal erosion in West Point in 2008 (left) and 2021 (right)

Source: Maxar Technologies; Google Earth

Citation retrieved from Fearing the tide: The resettlement debate in West Point, Liberia, https://www.urbanafrica.net/urban-voices/fearing-tide-resettlement-debate-west-point-liberia/accessed on 13 September 2020.

Liberian law and policy context does not offer specifics as to the process of a planned relocation. In particular, several critical aspects are absent. Liberian law does not recognize the need for consent and meaningful consultations with those to be relocated, it does recognize the need for assisting relocated populations in their efforts to improve their livelihoods and standards of living or at least to restore them, and does not discuss the need for the relocation, depending on Citation retrieved from Fearing the tide: The resettlement debate in West Point, Liberia, https://www.urbanafrica.net/urban-voices/fearing-tide-resettlement-debate-west-point-liberia/accessed on 13 September 2020.

In the absence of a clear strategy and national policy, successive administrations in Monrovia have attempted the planned relocation of West Point without success. Concerns that the relocation would place residents far from the jobs and amenities found in proximity to Monrovia’s center have stalled the relocation plans. Data from community-led surveys and conversations with community members highlighted the importance of social networks, economic activities, and livelihood opportunities in the settlement. In the absence of durable solutions, the residents’ efforts to preserve these opportunities in instances of environmental risk consist of constant micro-movements within the neighborhood, rather than movements to other parts, and neighborhoods of the city. Additionally, initial concerns about a relocation process that has so far failed to incorporate people’s needs have intensified given the issues faced by the first few households that did relocate through government housing assistance at the outskirts of the city in 2016. Given the low income of residents and the absence of jobs, transportation, and services in peri-urban Monrovia, the relocated households face serious challenges due to reductions in their livelihoods, without witnessing promised improvements in their living conditions. While sea erosion is perhaps not any longer a threat, the level of socioeconomic vulnerability of those relocated remains high.

The situation brings to the forefront the difficult trade-offs that the city of Monrovia, as well as many other cities in Africa, will need to consider. Do processes of relocation for adapting to environmental stressors justify potential losses in city access and opportunities for low-income residents and migrants? Or should the limited resources of the city be devoted to interventions that protect populations in-situ, with respect to the locational preferences of households? Certainly, there is no single answer to the above questions. Nevertheless, given that neighborhoods such as West Point, often constitute the only areas where low-income households and migrants can settle, and take advantage of urban opportunities, planned relocations need to take into consideration not only the objective of minimizing exposure to environmental risks but equally, how they overall affect life prospects for relocated households. In order to do so, more attention and local knowledge are necessary to inform the implementation of mobility norms, and the ways they are translated and embedded in local contexts, particularly in their interaction with longstanding urban policies that aim to restrict mobility towards cities.

Communities in impoverished neighborhoods under environmental risk across cities in the region are actively responding to this call. Community self-enumerations and data collection processes provide a basis for a more ‘generative planning,’ one that pays attention to the way households in those neighborhoods tend to fashion plans and understand risk, as they experience it in their everyday lives. These data can and should provide the basis for the development of more pragmatic solutions for those having to move or flee due to climate. But far from simple data collection, these community-led efforts aim at a much greater claim for recognition and negotiation, an exercise in participatory citizenship. They reveal the wish for belonging and membership, the necessity for deliberative processes that can transform knowledge from tacit to common.

Figure 1 Coastal erosion in West Point in 2008 (left) and 2021 (right)

Source: Slum/Shack Dwellers International, Know your City (2018) & Google Earth

Source: Slum/Shack Dwellers International

If the complexity of environmental migration is to be captured, the solutions to the challenges posed by mobility should be developed and formulated with the strong involvement of the affected populations, and anchored in their local contexts. The ability to effectively harness the opportunities and address the challenges associated with environmental migration is predicated on knowledge that is: “practical, collective and strongly rooted in a particular place” and that forms an “organized body of thought based on immediacy of experience” Geertz’s (1983: 75). This approach responds to the recognized need for the better inclusion of affected populations in environmental mobility research and the use of multiple knowledge systems, including the knowledge of both mobile populations and destination communities, in building a stronger evidence – base. This approach is particularly important for African cities where the dearth of data has historically impeded the ability of governments to improve migration prospects and the living conditions in origin and destination areas.